The Park City-County Board of Health, in a January 22nd meeting led by chair Dr. Stefanie Lange, voted to scrap a 2014 quarantine and isolation plan previously adopted to supplement the county’s emergency response plan. The highly anticipated meeting had been rescheduled from the previous week in reaction to threats allegedly aimed at public officials through the social media platform Facebook.

In a statement provided by Park County Undersheriff Tad Dykstra, Health Officer Laurel Desnick “Approached the Sheriff’s office stating that there had been personal attacks on Facebook towards individuals and the Health Department. The Health Department decided that it would be advantageous to cancel the health board meeting and prepare for a larger crowd.” Dykstra expanded on this statement saying that, “At this time, no criminal threats have been reported, and no investigation is being conducted.”

The Health Department and County Commissioner Bryan Wells were contacted by the Journal and asked to provide additional commentary on the cancellation, though neither responded prior to the rescheduled meeting.

The decision to rescind the plan, recommended by Health Officer Laurel Desnick, came after months of intense public scrutiny surrounding a separate draft presented at a health board meeting in October 2024. The draft contained controversial language concerning procedural measures for enforcing quarantine and isolation practices in the event of a communicable disease outbreak. Many in attendance at the October 8th meeting claimed that the plan was unconstitutional, illegal and potentially subject to litigation, sentiments since echoed online and during the meeting held on January 22nd.

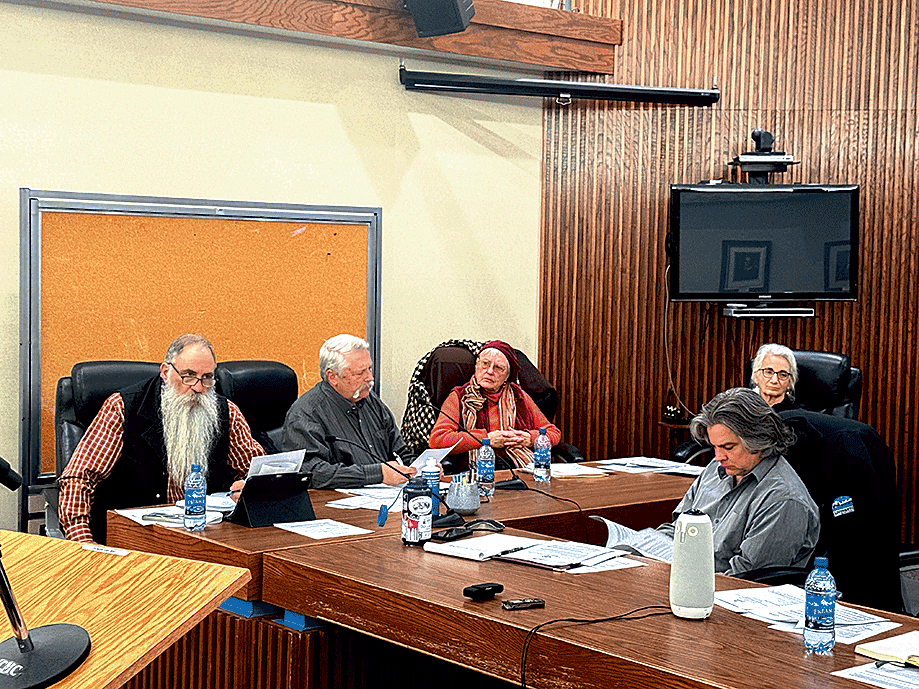

Last week, Park County citizens began trickling into the district courtroom well before 5 pm. By 5:30 pm the room was packed with nearly 100 people stewing in a palpable tension acknowledged by mediator Mary Anne Keyes, who kicked off the meeting shortly thereafter with opening statements about how Montana’s renowned “sunshine laws” enabled and encouraged extensive participation in the political process—especially, at the local level, where the implications of public policy resonate with a special fervor for American democracy.

Keyes then described how the evening’s proceedings would unfold in accordance with legal requirements and referred to a handwritten code of conduct plastered to the wall—rules of engagement intended to inspire civil discourse regarding the hotly contested topic, designed to temper public commentary—yet with only partial success.

Much of the ensuing contributions on “items not included within the agenda” (primarily the tabled draft presented October 8th) would go on to blatantly violate a rule prohibiting duplicative commentary in favor of individualized expression—ironically mimicking the issue at hand: obstinately exercising personal freedom at the expense of public welfare, a cynical recalcitrance displayed in response to purported misinformation propagated by federal officials during the COVID-19 pandemic, whether merely perceived or actual being irrelevant to the point.

An onslaught of unrelenting troops—government naysayers and enthusiasts, religious fanatics, conspiracy theorists, professionals from various educational backgrounds, local business owners and the like—feverously charged the podium to launch a grueling barrage of grievances hurled both in support and criticism of the health board for either abusing its authority in an attempt to wield power over the public or, scrupulously protect the community—depending on, of course, who you asked.

One speaker voiced support for the competence and expertise of health department officials by likening their role of protecting the public as “neighbors performing a service” to civil engineers and mechanics building infrastructure and repairing vehicles. Later that evening a second individual quipped, “No mechanic has ever come to my house and told me there was something wrong my car,” insisting instead that consulting professionals is sometimes necessary, yet whether intervention is sought remains a choice.

Though insightful contributions were put forth by Park County’s finest, many comments tediously overstated civil liberties infringements, vague and broad language used in legal documents, government overreaches of power, individual autonomy and the like—undoubtedly crucial considerations on any democratic platform, yet in terms of quality, not quantity.

The grossly redundant effort, nonetheless, would prove futile.

Because following nearly two and a half hours of public commentary, the board began its discussion with Desnick declaring the 2014 quarantine and isolation plan outdated due to it containing obsolete language and laws within the Montana Code Annotated (MCA) no longer enforceable.

Following the cancelled meeting scheduled for January 15th, the health board, according to Desnick, asked that she attempt to gather further information regarding current practices implemented by county health departments throughout Montana and to locate the previous quarantine and isolation plan originally drafted in 2004 (since updated in 2014)—solutions to “address missing information and misinformation,” said Desnick.

After consulting other public health officials, she learned that many departments have transitioned to using Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions (NPIs) as the “standard operating procedure for directing health department staff during situations where the spread of communicable disease puts the citizens of Park County at risk.”

Desnick then located Park County’s NPI, a document outlining “non-pharmaceutical interventions for disease, injury and exposure control,” completed and approved in 2019 as a required assignment from the Montana Department of Health and Human Services. At that time the plan was endorsed by the City of Livingston’s police department and Park County’s Sheriff’s department. The NPI complies with Montana code and DHHS standards.

Desnick stated “It would be reasonable for the board to vote to rescind that plan [the 2014 Quarantine and Isolation plan] immediately.” She also insisted that the draft presented on October 8th is “no longer relevant and it is reasonable to withdraw it.”

Board member Billy Watson and members of the public then openly questioned Desnick about the NPI, specifically, why it had not been included on the evening’s agenda, mentioned prior to the meeting, nor discovered up until recently—reasons cited for questioning the health officer’s transparency and the department’s operations. Keyes, referring to the code of conduct, proclaimed Watson’s statement a personal attack, sparking further controversy regarding the process preventing inquiries and promoting censorship.

Desnick, defending herself as interim director (accepting the position merely 10 days prior to the meeting), clarified that the document had not come to her attention until very recently, further insisting that though chaotic and confusing, there were no malicious intentions by the health department.

She said, “I cannot defend what others have done before me, but those who have passed through the [health] department were committed, honest and truthful in doing the best they could. In 2014, there were no electronic records or notes; this [quarantine and isolation plan] was in the midst of a paper document that is 278 pages long. There’s no funny business, no bait and switch, no trying to keep things from the public. This [what it took to find the document] is hard work.”

She also explained that the draft disseminated in October by former director Shannan Piccolo was adopted from another county under the assumption that a new plan must be formulated from scratch, calling it “unfortunate.”

Eventually, the board unanimously voted to rescind the 2014 quarantine and isolation plan. Because the tabled draft presented October 8th was not included on the agenda, it could not be considered for further action, though it is currently inactive. Members of the board intend to review the NPI at a future meeting and discussed the possibility of hosting an open forum for the public to provide feedback on developing a new plan. The health department will, for the time being, refer to state guidelines on the issue of disease prevention.

Though free speech is at the pinnacle of our democracy and should be championed as such, individual liberties were prioritized at the cost of effective and efficient governing—perhaps compensatory for a perceived loss of power during the recent pandemic. The question now is whether this same impulse to reclaim such power will once again override reason when an occasion calling for prudence arises, beckoning grace yet instead forced to welcome rebellion for its own sake.

Just how far will the pendulum swing and at what price? Could and should representative democracy, like the aldermanic form of government, exist within Park County? The founding fathers may have been onto something when they forewent true democracy for republicanism.

A majority of those who spoke abandoned post long before the board began their discussion or arrived at a decision—in my estimate nearly 70% or more of those in attendance at 5:30 pm had vacated the building altogether by 8 pm—inspiring curiosity amongst us remaining faithful as to what motivated this outcry: socio-political activism or self-aggrandizement? And in what other future scenario can we expect the common good be sacrificed for moral grandstanding? I’ll defer here to the Aristotelian ethos that virtue lies in moderation, the truest pursuit of democracy.

The Department of Health and its board members are certainly no less responsible for this mess. Lack of open communication channels and knowledge of processes (for example, requiring the presence of a mediator to oversee proceedings) further served to cause dismay and frustration. Whether elected or appointed, public officials are expected to correspond with media sources, engage in transparent public relations and understand basic democratic procedures—that is, if they are interested in promoting integrity amongst their constituents and governing conscientiously with dexterity.