by Nurse Jill

We have already had a look at the first two components of CPR: rescue breathing and compressions. But there is a final component that is the unsung hero of cardiac arrest. The defibrillator.

Every muscle cell in the heart must work together in an organized rhythm that allows for an effective contraction. The blood (and oxygen it carries) will only move forward in the circulatory system if all the muscle works together. These cells are stimulated to contract with an internal electrical stimulus. This smooth top-to-bottom electrical signal is what you see as an ECG in the hospital, and it is what controls the coordinated and all-together-now contraction of the heart muscle cells.

When the heart suffers trauma (such as loss of blood, blockage of its arteries, or a blunt force) that electrical rhythm is interrupted, and the electricity becomes random and frantic. This is called fibrillation. The result is that each individual muscle cell in the heart begins to contract independently from all the other cells because there is no longer a singular strong electrical impulse stimulating the cells in turn. The heart is literally at a standstill in the chest just quivering.

No teamwork among the heart cells means no contraction. No contraction means no blood being moved forward. And no blood moving forward means no pulse. Effective CPR will get blood moving to important areas for a time, but it will not solve the problem of fibrillation. The only way to solve fibrillation is to restart the central electrical impulse to restore the organized contraction of the heart once again. The heart must be de-fibrillated. And to do that we must use a defibrillator.

It is a common misconception that when a person is “shocked” it restarts the heart. This is perpetuated by the ever present (false) medical scene in movies where a victim has a flatline ECG on the monitor and the actors shock the victim back to life.

Defibrillators deliver a dose of electricity to actually stop the heart, not restart it. On the monitor this looks like a chaotic up and down line not a flat line. If the erratic electrical spasms are stopped it allows all the muscle cells to pause for a very brief moment. When they are paused the true, organized, central electrical impulse can restart and the cells will be calm enough to pick up on it and, hopefully, begin again their regular beat to sustain life.

This idea was first considered by scientists trying to figure out why the newly available electricity was killing people in the 1870s. In 1899, scientists Prevost, Battelli, and Cunningham discovered that an electrical shock not only “stopped” an animal’s heart but would also “restart” it if the shock was given again. The “stopping” and “starting” was in reference to fibrillation (stopped) and a regular healthy rhythm (restarted). This was the very beginning of the common lifesaving practice of defibrillation.

The actual first human defibrillation was in 1947 on a 14-year-old boy. The attempt was successful, and the boy fully recovered. This event gained worldwide recognition and renewed the research efforts to fine-tune this new technology.

The biggest problem was portability. The units that provided the electric shock were large and bulky making it difficult to store, move, and utilize in everyday hospital scenarios. They were a far cry from the compact and easily moveable modern models. Early models weighed 250 pounds which researchers were able to shrink to 45 pounds by 1961.

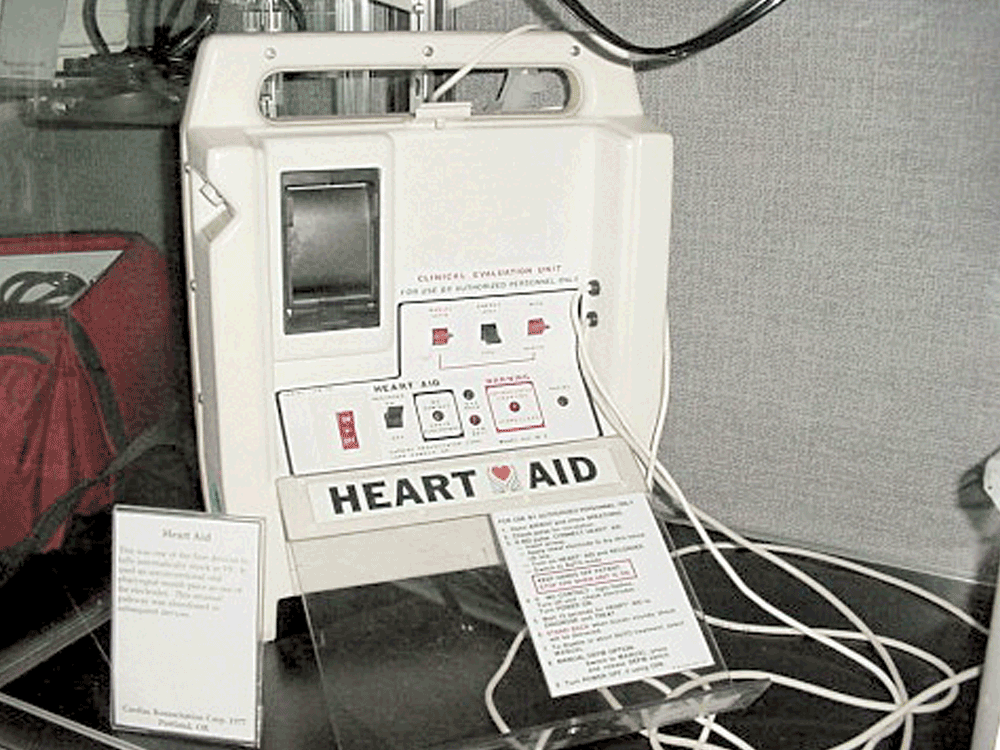

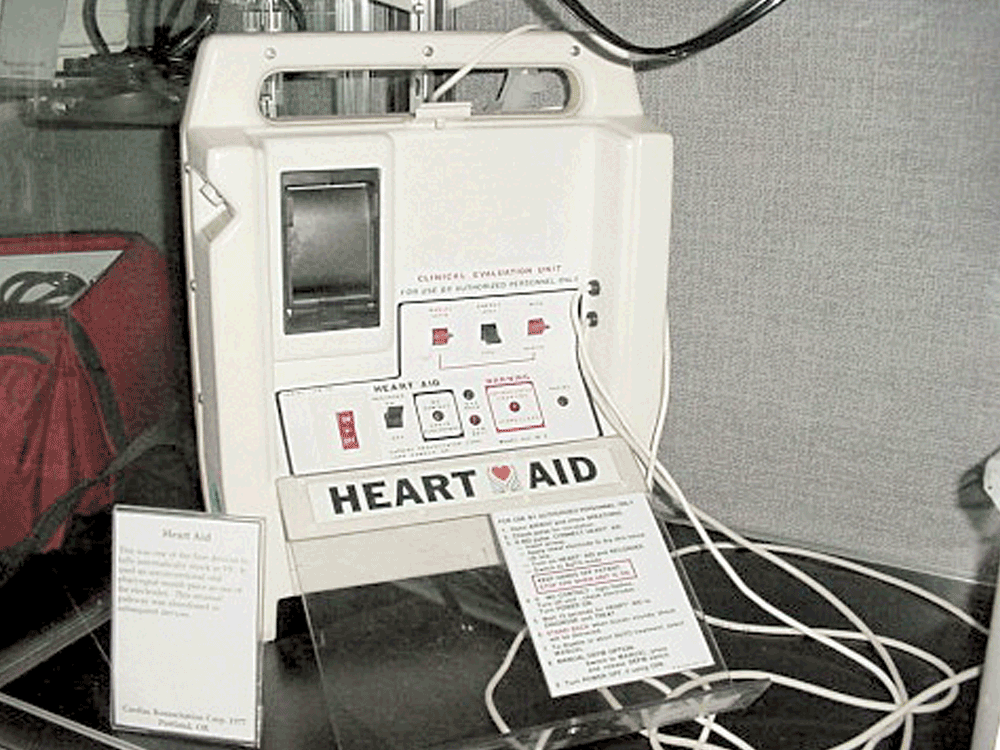

In 1978, doctors pioneered a more portable device that was safe for bystanders to use with a minimal amount of training called the Heart Aid. However it utilized an electrode going into the mouth which caused many concerns for side effects of vomiting and esophageal spasm.

Fast forward to today and we have a truly portable AED that usually weighs less than 5 pounds and has easy patches that stick to the chest of the victim. An AED is a simple straight forward device that has voice instructions to guide any user through the process of defibrillating a patient.

Rescue breathing, compressions, and AED (defibrillation) are all parts of reviving someone suffering from cardiac arrest. Despite our ancestors’ beliefs, the breathing is the least important in most situations. Most community CPR classes now teach just compressions and AED operation. No mouth-to-mouth necessary in many cases.

According to the American Red Cross over 350,000 people experience a situation that needs CPR each year. Of those, 70% happen in the home. They estimate that for every minute CPR (and defibrillation) is delayed it decreases the chance of survival by 10%.

Hopefully you never encounter a situation that requires CPR or an AED but just like wearing your seatbelt is an assurance against the “what-if” so is CPR. What if your loved one is a part of the 70%? What if your coworker collapses? With a few easy-to-learn skills you can be prepared. So get certified. You might be the next hero.